At first glance, it looks like a small hill made by nature. But if this tree-covered high ground in Wilson County could talk, it would say quite a bit. It would probably tell visitors that it wasn’t made the way most hills are made, but by people who lived here nearly a thousand years ago. We don’t have any idea what they called this place back then, but today we call it Sellars Farm State Archaeological Area. There’s a short loop trail that takes you around Sellars Farm. We walked the trail along with kids from the Boys and Girls Club of Rutherford County.

As you know, “prehistoric” refers to things that took place before the people and societies referred to had a written language. Sellars Farm contains the remains of a Native American community that existed in prehistoric time and was abandoned by the time European settlers arrived in Middle Tennessee.

Sellars Farm isn’t the only one of its kind, by no means. People have discovered the remains of Native American mound communities all over Tennessee that were apparently built and occupied long before European settlers got here. Most of these mounds have been destroyed over the years, cleared by farmers or by people building highways or new buildings. Sellars Farm is one of the few mounds in Tennessee that is protected under government ownership (among the others are Pinson Mounds in Madison County and at Harpeth River in Cheatham County).

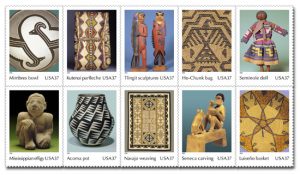

Based on the things that have been found in the ground at Sellars Farm, this community appears to have been occupied during the Mississippian Period, which goes from around 900 AD until about 1500 AD. During this period, the domestication of corn led to huge changes, many Native American tribes began making complex objects, and a social system became organized.

By the way, Sellars Farm is much newer than Pinson Mounds, which was primarily a Woodland-era establishment (the Woodland era went from about 1000 BC until about 900 AD). Sellars Farm is, however, similar in age to the abandoned mound community at Harpeth River State Park. And this wasn’t one of the bigger communities at that time. During the Mississippian period, there was a much larger community in present-day Alabama (a place now known as Moundville).

So what types of things have been found at Sellars Farm? A good question. In 1939 a farmer dug up four statues on the Sellars Farm property. These statues were made between 600 to 800 years ago. If you think about it, the very existence of these statues tells you something about the Sellars Farm community. It tells you, for instance, that some of the people there, or that some of the people they traded with, had learned how to carve complex objects out of stone.

We don’t know exactly what these statues were used for. But when de Soto’s army invaded the New World, they found many mound communities such as Sellars Farm, and noted that in some places, small statues such as these were used in religious ceremonies that marked occasions such as planting and harvest.

We also have no idea as to why these amazing objects were left behind when the Sellars Farm site became uninhabited. Were they intentionally buried? Was everyone killed in a military engagement? Did everyone suddenly die of disease? We don’t know. But the evidence suggests that there were Native American communities in places such as this one all over Middle Tennessee until about 1500 or so. Sometime after then, most of them left, or died, or some of both.

By the way, these statues are now housed at the McClung Museum in Knoxville.

Now, back to the Sellars Farm trail, which starts at the parking lot and does about a mile loop. As you walk the trail, you will notice that, like practically all Native American communities, this one was located next to a body of water. Spring Creek, a tributary of the Cumberland River, winds around the site of the village. Today we can ascertain that the creek provided several things for the village: food, mussel shells for use in pottery, and some degree of natural defense (the creek surrounds the village on three sides).

The main mound was made by hand — one

basketful of dirt at a time.

This photo was taken in the winter, which is the

best time to go look at mounds.

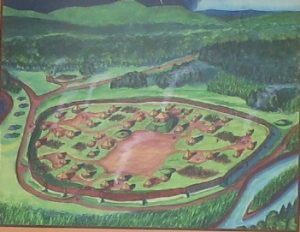

When the trail emerges from the woods, you can see the main mound. Today it is now covered with trees, but it would not have been covered with trees when this community was occupied. Why would the people who lived here in prehistoric times have built mounds, you might ask? Here is what archeologists think: Most of the mounds were built to house the most important structures in a community — structures that might be compared to a modern-day church or courthouse. Perhaps the idea was to make the important structure higher than all the rest — so you could see the structure from further away, and see further away from the structure. But in any case, mounds were built for the authority figures. They were, in all likelihood, places where only important people could go.

For some reason, people seem to be of the impression that people were buried in mounds. Usually that was not the case.

Perhaps the best way to think of mounds is to make an analogy with a modern-day town or city. Let’s say that you are standing in Nashville or Memphis. What can you see on the horizon? Big buildings, right? If you are standing near the center of Murfreesboro or Clarksville or Jonesborough, what can you see on the horizon? The big, tall, tower of the courthouse. As best we can tell, mounds, and the structures on top of them, were meant to have the same effect.

What else can you see at Sellars Farm?

First of all, if you come to Sellars Farm in the winter months (when you can see the ground, as opposed to tall grass and poison ivy), you might be able to see small mounds that are all over the place. At one time there were nearly 100 small mounds, and most of them are believed to have been the site of small houses with thatched roofs. These mounds haven’t been excavated by archaeologists in years, but in the 1800s an archaeologist from Harvard found pottery, pipes, eating utensils and other things here.

The other thing that is notable about Sellars Farm is that it once contained a ditch and a fence of wooden stakes for defensive purposes (known as a palisade) that wound around the inner village. Archaelogists believe that this palisade was built long after the community became inhabited. The fence tell us that the people who lived here were, at some point, worried about being attacked.

If you would like to organize a group tour to Sellars Farm, we suggest you either contact the friends group by calling Long Hunter State Park (which is near Sellars Farm and which administratively runs Sellars Farm). If, on the other hand, you wish to visit the park by yourself, here are the directions to it:

From Interstate 40 (in Wilson County) take exit 239. Turn east on highway 70, as if you are going to Watertown. Go about a mile. Then, turn left on Poplar Hill Road. Go a few hundred yards. The trailhead is on the left.

Thanks to State Archaeologists Mike Moore and Aaron Deter-Wolf and Park Ranger Thurman Mullins for their assistance in creating this virtual tour.