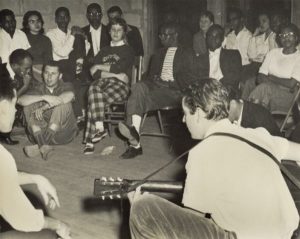

This photo, taken by an FBI agent, shows Martin Luther King Jr., Pete Seeger,Rosa Parks and Ralph Abernathy at Highlander in 1957.

PHOTO: Highlander Research and Education Center

When people think of the Civil Rights Movement, they often think of Selma, Montgomery, Atlanta or Memphis. Maybe they should think of Grundy County, Tennessee.

After all, it was at the Highlander Folk School in Grundy County where early civil rights strategy was mapped out. At Highlander, white and black activists — including as Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks — regularly met in the 1950s and talked about how they might change the South, and here that many people trained for the Civil Rights Movement.

Because it was so controversial, the Highlander Folk School was shut down by the state government and its assets seized. However, a successor organization, known as the Highlander Research and Education Center, still exists in East Tennessee.

This tour will take you to both places.

Myles Horton and Eleanor Roosevelt standing on the porch of the main building at Highlander

PHOTO: Highlander Research and Education Center

There are many books and documentaries about the Highlander Folk School. The institution was founded in 1932 by Myles Horton, a native of Savannah, Tennessee, who was educated at Cumberland University in Lebanon and Union Theological Seminary in New York. In the 1920s, Horton travelled to Denmark and was impressed with the concept of the Danish Folk School, an institution where ordinary people learned everything from agricultural methods to how to read. Upon his return to the United States, he looked for a place to start something loosely based on this idea. A retired college professor named Dr. Lillian Johnson donated mountaintop land in Grundy County to the cause.

Horton’s ideas were, by standards of his time, radical. He believed in racial integration at a time when integrated events and schools were illegal. He also believed that workers of various kinds, whether in factories or mines, should organize in labor unions, something to which business leaders were opposed.

At the time of Highlander’s founding, Horton became involved in the Wilder coal mining strike. In 1932, miners in Fentress County went on strike to protest low pay and unsafe working conditions. The company hired replacement workers (derogatorily referred to as scabs) to work the mines, but during the next few months several of the bridges used to haul coal from the mines were damaged or destroyed, and there were numerous violent incidents against strikers and scabs.

After things began getting violent, Myles Horton warned union president Barney Graham to leave. Graham ignored Horton’s advice and, on April 30, 1933, was shot and killed by company guards in broad daylight.

No one was ever convicted of Graham’s murder. “If I hadn’t already been a radical, that would have made me a radical right then,” Horton later wrote.

Horton certainly was a radical, by standards of his time. In the 1930s, Highlander was involved in attempts to organize labor unions all over the South. In the eyes of many people, such activism was communist. In 1939, the Nashville Tennessean newspaper sent a reporter to spend several days at the school; he lied and told members of the school he was a teacher. A few weeks later, in a six-part series on the front page of the newspaper, the reporter concluded that Highlander was “a center, if not the center, for the spreading of communist doctrine in the South.” Horton denied that he was a communist, and many of Highlander’s allies responded with angry letters to the Tennessean.

In 1952, Highlander shifted its focus from labor organizing to civil rights issues such as voter registration and desegregation.

Horton later pointed out that Highlander didn’t so much “train” people in how to work for civil rights; it got people together in a setting where they could talk it out, and the method naturally came out of that. “We had made the decision to do something about racism — we were having workshops with black and white people to figure out some answers — but we didn’t know how to tackle the problem,” he wrote in his autobiography. “The Highlander staff didn’t approach it theoretically or intellectually, they just decided to get the people together and trust that the solution would arise from them.” During the 1950s, among those who attended training sessions at Highlander were King, Parks, Septima Clark, Ralph Abernathy, James Bevel and many others.

At Highlander, participants met in small groups and talked about what they wanted to change about society, how they might organize change and how they might change people’s minds about change. The type of protest method that was taught was non-violent in nature. It was at Highlander Folk School that the song “We Shall Overcome” became a symbol for the Civil Rights Movement.

As the movement began, many southern newspapers that were opposed to the movement blamed Highlander (much as newspapers had blamed Highlander for labor unrest two decades earlier).

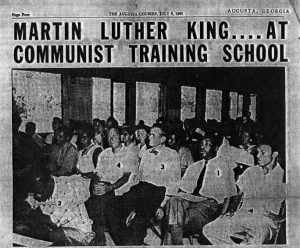

In 1957, King attended a weekend event in honor of Highlander’s 25th anniversary. Among those in attendance were representatives of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, looking for proof that King and Highlander were breaking the law. A few weeks later, the Georgia Commission on Education published a pamphlet entitled “Highlander Folk School: Communist Training School, Monteagle, Tennessee.” This pamphlet claimed that there was ample proof that Highlander, as well as the entire Civil Rights Movement, was communist in origin.

Horton argued otherwise. “Highlander did not and does not welcome enrollment of anyone with a totalitarian philosophy, whether from the extreme right or the extreme left,” he said. “The attempt of the Georgia governor’s commission to draw from the serious and fruitful deliberations of this gathering sustenance for the efforts of Southern racists to equate desegregation with communism evokes our strong condemation.”

Myles Horton and Eleanor Roosevelt standing on the porch of the main building at Highlander

PHOTO: Highlander Research and Education Center

Among the people who came to Highlander’s defense at this point was Eleanor Roosevelt, who gave Highlander a check for $100 and visited the school.

Today, these types of accusations might seem bizarre and paranoid. But in the 1950s — the era of McCarthyism in the U.S. — people felt differently. In 1959, the Tennessee General Assembly conducted an investigation of Highlander that eventually led to the place being padlocked and closed. “You can padlock a building, but you can’t padlock an idea,” Horton said to reporters on the day that the sheriff took over the property.

By this time, the Civil Rights Movement had, in fact, become an idea that could not be padlocked.

All the property that the Highlander Folk School owned in Grundy County — land, buildings, pond, books — was eventually taken over by the government, which subdivided the land and auctioned it off.

Today, many of the structures that were used by Highlander prior to 1959 — such as the library building — are still standing. However, the main Highlander building (which had once been Dr. Lillian Johnson’s home) burned down years ago. There is nothing left of it except a stone foundation.

A few years later, Horton organized a successor to the Highlander Folk School. Located in Jefferson County, the Highlander Research and Education Center picked up where the Highlander Folk School left off. According to its website, it is involved in “grassroots organizing and movement building in Appalachia and the South.”

Myles Horton remained active in Highlander until his death in 1990. He was buried at the cemetery adjacent to the original Highlander site, in a grave next to those of his wife and his parents.

(One more tidbit: In 2014, the former Highlander property in Grundy County was purchased by the Tennessee Preservation Trust, which is now trying to raise money to secure the property and convert it into something that would be permanently open to the public. More on this as we learn it!)