Teacher’s note: Click here for a pdf quiz about this section of the website.

When we think of an immigration, we often visualize a movement that happened one person or one family at a time.

In the 1870s, a migration of African Americans from Tennessee to Kansas and Missouri occurred practically overnight and because of one man. The people who followed him were part of a larger movement known as the Exodusters.

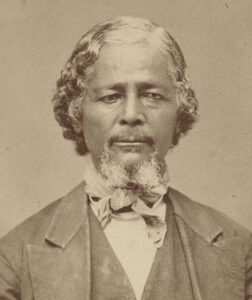

Benjamin “Pap” Singleton was born into slavery in Middle Tennessee in 1809 and escaped to the North when he was 37 years old.

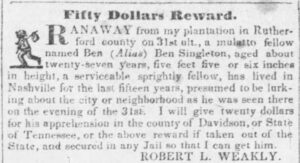

Singleton’s slaveholder was a Rutherford County man named Robert Weakly who published an ad when Singleton ran away. In the ad, Singleton is referred to as “mulatto,” which means one of his parents was black and the other was white.

After the Civil War, Singleton moved back to Tennessee and went to work as a cabinet and coffin maker. By the mid-1870s, he became convinced that black people would never receive fair treatment in the South.

“The whites had the lands and the blacks nothin’ but their freedom,” he later told a Congressional committee. “By and by the Fifteenth Amendment came along, and the carpetbaggers and my poor people thought they was going to have Canaan right off. But I knowed better.”

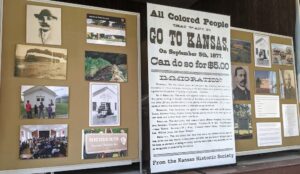

In 1874, Singleton and a Sumner County minister named Columbus Johnson founded the Edgefield Real Estate and Homestead Association. It went into the business of moving African Americans to Kansas. “Brethen, friends & Fellow Citizens,” one of the company’s ads said. “I feel thankful to inform you that the Real Estate and Homestead Association will leave here the 15th of April 1878 in pursuit of homes in the southwestern lands of America, at transportation rates cheaper than ever was known before.”

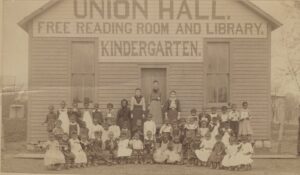

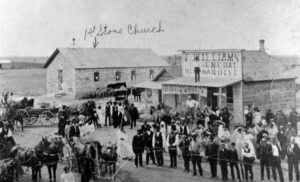

The people pictured here, in Dunlap, Kansas, were probably born enslaved in Tennessee and moved to Kansas because of Pap Singleton. (Kansas Historical Society photo)

Why Kansas? It had plenty of vacant land and few people. The Homestead Act of 1862 said that any U.S. citizen could own 160 acres there if they lived on the land for five years, farmed it, and built a home on it.

There was also something symbolic about the state which had produced abolitionists such as John Brown.

It should also be pointed out that there were former slaves migrating to Kansas from other parts of the South by this time (more on that later.)

A photo of thousands of Exodusters leaving Nashville, with Singleton and Johnson in the foreground (Library of Congress photo)

In 1878 and 1879, hundreds of African Americans boarded steamboats in Nashville. From there they migrated to Kansas towns such as Dunlap, Parsons, Lawrence and Topeka. Under Singleton’s leadership, as many as 10,000 people left Tennessee for Kansas in this manner.

The mass migration of African Americans from Tennessee to Kansas inspired similar migrations from and to other states. Large numbers of former slaves and their children left states such as Kentucky, Mississippi, Texas, Georgia and Louisiana for destinations in Kansas, Missouri, Colorado and Oklahoma. All in all, about 40,000 of the formerly enslaved left the South as part of this movement.

How did these migrants make out? Most had a hard time and were unprepared for the flat, treeless plains. Many of the migrants lived in dugout homes — which means they were practically living underground for a time, as was the case with a lot of Kansas pioneers.

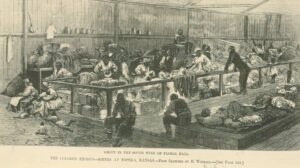

This sketch in Harper’s Weekly, published in 1879, shows some of the Exodusters living in a communal shelter in Topeka, Kansas.

Some didn’t remain in rural Kansas for long, run off by the lack of water, blizzards, prairie fires and other difficulties of life in that part of the country. “Considerable suffering is reported among the exodusters here,” reported the Parsons [Kansas] Weekly Sun on January 15, 1880. Many of the citizens of Kansas were not happy about the migration. “We want it understood that the exodus is a curse to Kansas,” the Burlington Independent said. “It is a weary and loathsome burden to the people.”

As you can see from this satellite image, there isn’t anything left of Dunlap, Kansas, except a cemetery.

Some of the places settled by former slaves from Tennessee are now abandoned, such as Dunlap. (In fact, the only thing left of Dunlap is a cemetery in which many people originally from Tennessee are buried.)

However, some of the Exodusters remained in places such as St. Louis, Missouri, and Topeka, Kansas. To this day, there is a part of Topeka known as Tennessee Town because of the large number of former enslaved people who migrated there after the Civil War.

In fact, some of the descendants of the Tennesseans who moved to Topeka were among the many plaintiffs in the Brown v. Board of Education legal case which went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. That case resulted in the integration of public schools all over the country and is considered to be one of the most important decisions in the U.S. Supreme Court’s history.

Today, there are a few abandoned “ghost towns” where African-American migrants once lived, but where almost no one lives now.

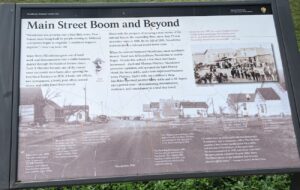

The best preserved is Nicodemus. In 1877 a group of seven men, six of whom were black, founded the town of Nicodemus, Kansas, for former slaves. In the 1880s, more than 700 people lived there—most of them African-American migrants from Kentucky.

Nicodemus would fade in population because a railroad was built in that part of Kansas which bypassed the town. Today the township’s population is about 45, but several of the buildings are preserved as part of a national historic site. (See right column for photos we took when we visited Nicodemus in May 2021.)