Every September 25, re-enactors meet at

Sycamore Shoals, from where they journey to

Kings Mountain.

PHOTO: Overmountain Victory Trail Association

It was the most famous road trip and the most important victory in Tennessee history.

During the American Revolution, a British commander named Patrick Ferguson led an army through South Carolina. Along the way, he sent a threatening message to the Scotch-Irish settlers west of the mountains, including the ones in present-day northeast Tennessee.

This message angered the settlers. About 480 of them left their homes, crossed the mountains and joined other groups of settlers from Virginia and the Carolinas. This rag-tag army surrounded Ferguson’s army on a small ridge called Kings Mountain.

Ferguson’s army was crushed, Ferguson killed, in what some consider the turning point of the American Revolution.

This map at Kings Mountain National Military Parkshows how forces allied to Britain moved through South Carolina

Here are the events that led to this battle:

War between Britain and its American colony started in 1775 and dragged on much longer than Britain thought it would. Although armies consisting of redcoats (British soldiers) and Tories (American colonists loyal to Britain) won many battles in and around Boston, New York and Philadelphia, the British could not make the American army surrender.

In 1778, the British started a new campaign referred to as the “southern strategy.” The idea was to invade Georgia and move north from there. The British believed that more colonials (Americans) were loyal in the South, which would help the invasion succeed.

From the British point of view, the southern strategy got off to a great start, with the takeover of Savannah, Georgia, in 1778 and Charleston in 1780. By the summer of that year the British forces moved north through South Carolina in three parts, led by Lord Charles Cornwallis, Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton and Major Patrick Ferguson.

As armies fighting for Britain worked their way through South Carolina, they fought and defeated rebellious colonials that they found along the way. These were not huge battles, by standards set by the American Civil War a century later. But they were bloody, ugly affairs in which awful things happened.

On May 29, in a part of South Carolina known as the Waxhaws, a loyalist force led by Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton defeated a larger force of Americans under Abraham Buford. When Buford’s men tried to surrender, they were slaughtered by Tarleton’s army. Out of 400 men, 113 were killed, and 150 were so badly wounded that they could not be moved from the field.

People who lived in the Waxhaws were horrified by what became known as “Buford’s Slaughter.”

For example, after Buford’s Slaughter, three teenage brothers who lived in the Waxhaws tried to join the rebellion. Two of them (Hugh and Robert) were killed in the war. The third brother, Andrew, survived the war and later moved to Tennessee.

Andrew Jackson would one day be President of the United States. He never forgave the British for what happened at the Waxhaws during the American Revolution.

Ferguson’s army was the westernmost of these three forces, and there is something interesting that many people don’t realize. He did not have a single soldier from Great Britain!

Ferguson started out with four regiments of Tory soldiers from New York, New Jersey and Connecticut. Along the way he recruited other men from the South Carolina countryside.

Some of the South Carolinians who joined Ferguson were loyal to the crown. Some of them fought with Ferguson because they thought the British would win the war. Some were forced to join at gunpoint.

As Ferguson’s army moved into North Carolina, he heard about the many Scotch-Irish immigrants who had crossed the mountains in defiance of King George III’s Proclamation of 1763. In September, he issued a written warning to the frontiersmen to lay down their arms or he would “lay waste to their country with fire and sword.”

Isaac Shelby, a leader in what is now Sullivan County, Tennessee, received this warning. He rode to meet with John Sevier, who was in Jonesborough at the time. Shelby and Sevier decided to try to raise an army that would link up with other rebellious forces and fight Ferguson before he moved west.

On September 25, these men gathered at the Sycamore Shoals of the Watauga River (present-day Elizabethton). There were 240 from Washington County, 240 from Sullivan County, and 400 from Virginia. Most of these men had no military training. None of them had uniforms. Some didn’t even have shoes!

But they were skilled with rifles. Many had previous experience fighting against Native Americans. And they were furious at Ferguson for issuing such a threat.

These men said goodbye to their wives, their sons and their daughters, not knowing if they would ever see them again.

The “Overmountain Men,” as they became known, crossed the mountains into North Carolina. We know the exact route that they took. Today we refer to this as the Overmountain Victory National Historic Trail, and you can follow this course through Tennessee, North Carolina and into South Carolina.

The weather did not cooperate. It rained the first night, and the Overmountain Men kept their gunpowder dry by putting it under a natural embankment called Shelving Rock.

They crossed the peak of the mountain range at Yellow Mountain Gap, which is now a stop along the Appalachian Trail.

However, very few of us alive today could do what they did. These men marched, walked and rode 330 miles in two weeks!

On September 30, the Overmountain Men were joined by other Americans from North Carolina and Virginia at a place called Quaker Meadows. A few days later, they tracked down Ferguson’s army on one of the few hills in that part of South Carolina.

Why Ferguson chose this hill, known by the locals as Kings Mountain, is a mystery to this day. Since Ferguson was from Scotland, which is mountainous, some historians think that he felt comfortable on top of hills. He clearly believed his forces would have a strategic advantage on top of the 60-foot hill.

The colonial forces split into groups and surrounded the mountain. Ferguson’s men lined up and prepared to defend themselves.

The battle that followed was not long or complicated.

The patriot forces yelled at the top of their lungs and charged up the hill. They fired, ducked behind the nearest rock or tree to reload, and fired again. They used tactics they had learned from fighting Native Americans on the frontier.

Ferguson’s men fired, and reloaded, and fired again. On at least two occasions, his men affixed bayonets to their rifles and charged down the hill. The Overmountain Men (who didn’t have the types of rifles on which bayonets can be afffixed) ran from the bayonets. But after Ferguson’s men headed back up to defend the top of the hill, the Overmountain Men chased them.

There are many first-person accounts of the battle.

There are many first-person accounts of the battle.

Here is what Thomas Young wrote:

“Ben Hollingsworth and I took right up the side of the mountain, and fought our way, from tree to tree, up to the summit. I recollect I stood behind one tree, and fired until the bark was nearly all knocked off, and my eyes pretty well filled with it. One fellow shaved me pretty close, for his bullet took a piece of my gun-stock. Before I was aware of it, I found myself apparently between my own regiment and the enemy.”

James Collins wrote:

“We were soon in motion, every man throwing four or five balls in his mouth to prevent thirst, to be in readiness to reload quick. The shot of the enemy soon began to pass over us like hail; the first shock was quickly over, and for my own part, I was soon in a profuse sweat. My lot happened to be in the center, where the severest part of the battle was fought. We soon attempted to climb the hill, but were fiercely charged upon and forced to fall back to our first position. We tried a second time, but met the same fate; the fight then seemed to become more furious. Their leader, Ferguson, came into full view, within rifle shot as if to encourage his men, who by this time were falling very fast; he soon disappeared. We took the hill a third time; the enemy gave way.”

Another soldier, Leonard Hice, was shot five times — twice in the left arm, once in his left leg, once in his right knee and once in the chest. He kept firing after the first two bullets, to his arm, and he did so by resting his rifle against a tree. “Whether my bullet brought the enemy down or not, I cannot say, for many were as good marksmen as I,” he later wrote.

Today, we believe that the men shooting from the bottom of the hill were more likely to hit their targets than the men shooting down at them, in part because of the rocks and trees they could hide behind.

About the time colonial soldiers made their way to the top of the hill, they killed Ferguson. (A later examination of the body revealed that the British commander had been shot seven times.) At that point, the battle became a real slaughter.

Captain Abraham DePeyster, who took command of the Tory forces at that point, tried to surrender as fast as he could. This wasn’t easily done, because some of the Americans continued to fire even after DePeyster tried to surrender — some not realizing the battle was over, and some to get revenge for Buford’s Massacre.

Collins later described the scene:

“After the fight was over, the situation of the poor Tories appeared to be really pitiable; the dead lay in heaps on all sides, while the groans of the wounded were heard in every direction. I could not help turning away from the scene before me, with horror, and though exhulting in victory, could not refrain from shedding tears.”

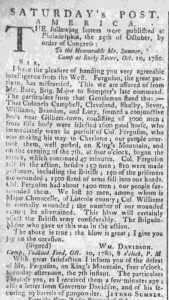

In all, 244 members of Ferguson’s army were killed, 163 were wounded and 688 were taken prisoner. Only 29 members of the patriot militia were killed and 58 wounded.

Coming at the time that it did, after British victories at Charleston, Camden and the Waxhaws, the Battle of Kings Mountain was a huge boost for the American side. Years later, a young historian named Theodore Roosevelt would write that “this brilliant victory marked the turning point in the American Revolution.”

Turning point or not, the victorious army didn’t stay in the field for long. Worried that Cornwallis might be nearby with a much larger force, and concerned they were needed at home to fight Native Americans, the Overmountain Men retreated back from where they came.

Cornwallis later resumed his military offensive in the south. But after Kings Mountain, people in the Carolinas were no longer joining the Tory cause.

Only a year later, Cornwallis surrendered to General Washington at Yorktown, ending the American Revolution.

And what became of the Overmountain Men from Tennessee who made such a huge difference in this battle? Some of them didn’t talk much about what happened at Kings Mountain. In David Crockett’s autobiography, for instance, he writes that his father John Crockett fought with the Overmountain Men at Kings Mountain. But his father apparently never talked about it.

However, two Kings Mountain veterans who did go on to have public lives were Isaac Shelby and John Sevier. Shelby move to Kentucky and became the first governor of that state. Shelbyville and Shelby County, Tennessee, are named for him.

John Sevier was elected governor of the short-lived state of Franklin and later became the first governor of Tennessee. Among the places named for him are Sevierville and Sevier County.

One final story about Kings Mountain: After the battle, Sevier chose a Washington County soldier named Joseph Greer to deliver the message about the battle to the American Congress. (Greer was born in Philadelphia, where Congress met at that time.) Greer, who was said to have been six foot six inches tall, made the journey by himself, avoiding hostile Native Americans and British soldiers the whole way.

When Greer got to Congress, the doorkeeper tried to bar his entrance. But the veteran of Kings Mountain pushed him aside and delivered the message to the representatives there, who were shocked and thrilled with the news.

“With soldiers like that,” George Washington said, “no wonder the frontiersmen won.”

Joseph Greer later moved to Lincoln County, where he lived until 1831. He was buried near the town of Petersburg.