How can an important place vanish from the map? In this virtual tour we will find out how it can, and did, happen.

If you drive west from Covington, in Tipton County, you will arrive at the Mississippi River at a place called Randolph. Today there is not much to it — an unincorporated community with a couple of churches, a handful of homes and a boat dock.

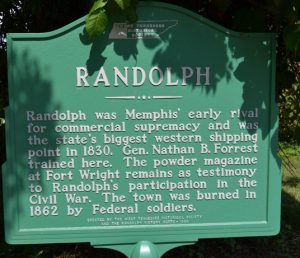

However, as you can see from this sign, there was a time when Randolph rivaled Memphis for commercial supremacy along the Mississippi River. Randolph lost out on that rivalry, fell victim to the destructive force of the Mississippi River, and was destroyed by the Union Army during the Civil War.

However, as you can see from this sign, there was a time when Randolph rivaled Memphis for commercial supremacy along the Mississippi River. Randolph lost out on that rivalry, fell victim to the destructive force of the Mississippi River, and was destroyed by the Union Army during the Civil War.

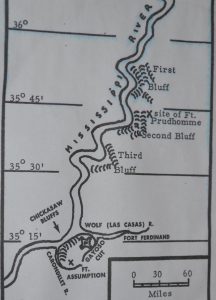

First, a bit about geography. There are four bluffs along the east side of the Mississippi River in what is now Tennessee. They were named by French explorers as they came downstream in the 1600s.

First, a bit about geography. There are four bluffs along the east side of the Mississippi River in what is now Tennessee. They were named by French explorers as they came downstream in the 1600s.

Since you are above flood waters and can see far from a bluff, these bluffs were considered good places to camp, build forts and build towns.

The “First Chickasaw Bluff” eventually became the site of Fort Pillow (in Lauderdale County). Randoph is located at the second bluff. The third bluff is located within the present boundaries of Meeman-Shelby Forest State Park. Downtown Memphis is on the “Fourth Chickasaw Bluff.”

In 1682, the French explorer La Salle led an expedition of about fifty people down the Mississippi River. He stopped on one of the Chickasaw Bluffs and built a stockade, naming it Fort Prudhomme after a missing member of his party. La Salle soon continued downstream, eventually making it all the way to the Gulf of Mexico.

In 1682, the French explorer La Salle led an expedition of about fifty people down the Mississippi River. He stopped on one of the Chickasaw Bluffs and built a stockade, naming it Fort Prudhomme after a missing member of his party. La Salle soon continued downstream, eventually making it all the way to the Gulf of Mexico.

Fort Prudhomme thus became the first structure built by whites in present-day West Tennessee. And although there are disagreements among historians, many believe it was located on the “Second Chickasaw Bluff,” meaning the eventual location of Randolph.

For the next 150 years, the only people who lived on the Second Chickasaw Bluff were Chickasaw Indians, although rafts frequently floated by in the late 1700s and early 1800s, carrying goods in the direction of New Orleans.

Then, in 1818, the United States government acquired what is now West Tennessee from the Chickasaw, resulting in the greatest land rush in Tennessee history. Since the Mississippi River was the route that would be taken by people in West Tennessee to get their goods to market, there were immediate movements to build towns along the river and take advantage of that trade.

The best-known of these real estate ventures was on the Fourth Chickasaw Bluff, where investors John Overton, James Winchester and Andrew Jackson founded Memphis.

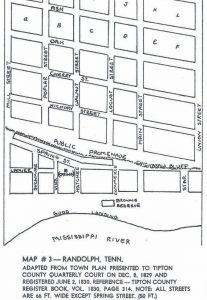

On the Second Chickasaw Bluff, investors started another town in 1823, naming it after Virginia Congressman John Randolph. Not only did Randolph have a good landing for Mississippi River flatboats, it was also only a couple of miles from where the Hatchie River merged with the Mississippi (a big deal, because the Hatchie is navigable as far inland as Bolivar.)

Randolph’s heyday was in the 1830s, when it shipped more cotton on the Mississippi River than did Memphis. If you had come through Randolph then you would have found about 1,000 residents, three warehouses, saloons, schools and four hotels, the nicest of which was known as Washington Hall. You would have also found a printing press that produced a newspaper called the Randolph Recorder.

Randolph’s heyday was in the 1830s, when it shipped more cotton on the Mississippi River than did Memphis. If you had come through Randolph then you would have found about 1,000 residents, three warehouses, saloons, schools and four hotels, the nicest of which was known as Washington Hall. You would have also found a printing press that produced a newspaper called the Randolph Recorder.

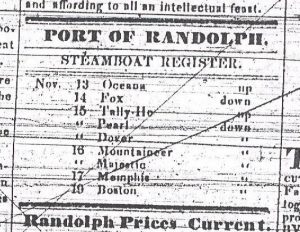

Incredibly, the Tennessee State Library and Archives still has a few back issues of the Recorder on microfilm. For several years it came out weekly, although in the summer of 1835 it suspended operations for a time because of a cholera epidemic. According to the Recorder, a new steamboat arrived in Randolph just about every day.

Between December 12 and 19, 1834, for example, the Recorder reported that 18 steamboats came through town, ten heading downstream the Mississippi, seven heading upstream, and one floating up the Hatchie. These boats traded everything from cotton and oats to nails and whiskey.

Many people came through Randolph during this era. Most were headed down the river, toward New Orleans, or up the river, in the direction of St. Louis. Many were heading west, to points west such as Arkansas and Texas. Some people stayed long enough to have been called residents.

Jesse Benton, a colorful character from early Tennessee history who dueled Tennessee Governor William Carroll and got in a brawl with Andrew Jackson, lived in Randolph for a time.

On November 13, 1833, people all over America stared at the sky as one of the largest meteor showers ever took place. People gazed at the sky in amazement and fear, some wondering if the world was coming to an end. Among the people who saw it from Randolph was Congressman David Crockett, who was visiting a friend at the time.

Today, there is nothing on or near the Second Chickasaw Bluff that indicates there was a town here in the early nineteenth century. If you come to Randolph today, you can find a small, paved county road that takes you directly to the river. Thanks to Randolph enthusiast Graydon Swisher, we found a wide path along the river (shown here) which we believe to be one of the original thoroughfares of Randolph.

Today, there is nothing on or near the Second Chickasaw Bluff that indicates there was a town here in the early nineteenth century. If you come to Randolph today, you can find a small, paved county road that takes you directly to the river. Thanks to Randolph enthusiast Graydon Swisher, we found a wide path along the river (shown here) which we believe to be one of the original thoroughfares of Randolph.

But that’s about it.

So why did Memphis thrive and Randolph vanish? There were several reasons.

So why did Memphis thrive and Randolph vanish? There were several reasons.

- For one thing, Memphis had more prominent founders (especially Andrew Jackson). This may have made a huge difference.

- In 1829, the federal government chose for its thrice per week mail line a route running from Nashville to Memphis, through Bolivar and Somerville. Randolph got mail only once per week.

- Randolph, unlike Memphis, never became the county seat. In 1834 the commissioners of Tipton County chose Covington as the place for the courthouse — a blow to Randolph.

-

Randolph’s early residents were also hoping for a canal to be built that would have connected the Tennessee River to the Hatchie River (David Crockett was involved in the attempt to develop this canal.) Had this canal been built, it might have meant an increase in business for Randolph. But President Andrew Jackson was against such federal improvements, and the project never materialized.

- In later years, Memphis got a rail connection to Charleston. Randolph never got a railroad of any kind.

As you can see, large parts of the”Second

Chickasaw Bluff” (Randolph) have

tumbled into the Mississippi River

over the years.

There is evidence that as the years went by it became clear that Memphis had superior geography; a “shelf” of sandstone beneath the layer of mud that made for more stable building foundations.

Meanwhile, in Randolph, the ground underneath people’s feet was giving way. One story about the fate of the town claims that by 1860:

“The surge of the river against the sandy bluff had undermined and carried away a large part of the town and had also caused the bluff to sink in several places as to form giant steps, acres in extent, and twenty or thirty feet above each other. Rains had washed frightful ravines down the giant steps and in one of these, called ‘the devil’s cellar,” was then large enough to hold Randolph and all its inhabitants.”

The idea that a town could be entirely eroded away by the Mississippi River may sound farfetched. But it happened in other places as well. Downstream from Randolph was once a thriving community called Napolean, Arkansas. In the 1840s and 1850s it completely collapsed into the Mississippi and vanished.

The Civil War had something to do with it as well.

The Civil War had something to do with it as well.

Many of Randolph’s buildings were still standing when the War Between the States broke out. Early in that conflict, the Confederate government knew it needed to do something to try to keep Memphis from falling into Union hands. Utilizing slave labor, it built two forts at Randolph: one known as Fort Randolph and the other known as Fort Wright (tearing down many of the town’s abandoned buildings in the process). The Confederate Army also operated boot camps here for soldiers throughout Tennessee; it was here that Private (later General) Nathan Bedford Forrest began military training.

The Confederate government didn’t have much of a Navy to help defend its fortifications along the Mississippi. Forts Randolph and Wright were abandoned by Confederate forces in the summer of 1862. A few months later, after rebel guerillas were traced to the area, General William T. Sherman, then in charge of the captured city of Memphis, ordered his army to burn what was left of Randolph to the ground.

Almost nothing is left of these Civil War fortifications other than an underground magazine where the Confederates stored gunpowder.

Finally, in 1886 a fire destroyed about a dozen houses and places of business that were still standing in Randolph, and most of the property owners didn’t have insurance at the time. “The Place About Wiped from the Face of the Earth,” read the headline in the [Memphis] Public Ledger (see article on the right).

Today, most of the land that was Randolph, Fort Randolph, and Fort Wright are located on private property, so you have to be careful about just showing up and exploring. However, the Tennessee Parks & Greenways Foundation has purchased a 19-acre tract where we believe the heart of Randolph to have been, and the Mississippi River Foundation is working on a plan to turn the place into a park and river center.

Today, most of the land that was Randolph, Fort Randolph, and Fort Wright are located on private property, so you have to be careful about just showing up and exploring. However, the Tennessee Parks & Greenways Foundation has purchased a 19-acre tract where we believe the heart of Randolph to have been, and the Mississippi River Foundation is working on a plan to turn the place into a park and river center.

Who knows? Maybe one day, archaeologists will even dig up some of the relics that are hopefully left behind at this interesting and unspoiled place on the Mississippi River — at least the relics that didn’t fall into and drift down the Mississippi River over the years.