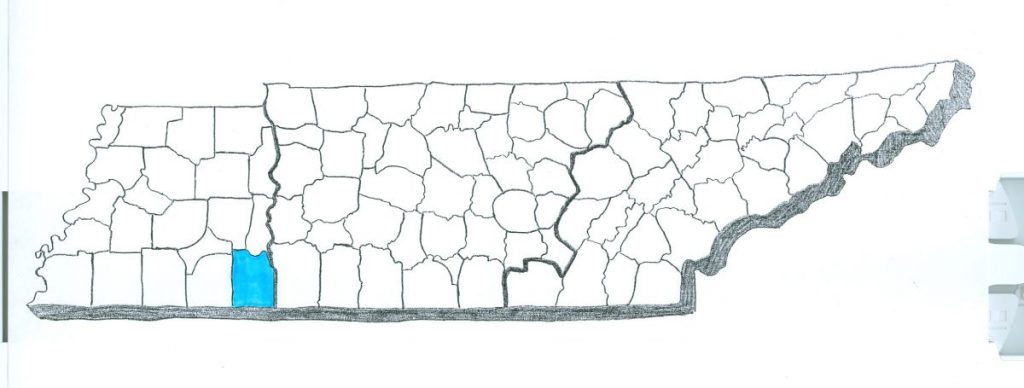

Before the Battle of Shiloh, many people believed that the Civil War wouldn’t last long. But on April 6 and 7, 1862, two massive armies collided on this out-of-the-way piece of land in Hardin County. By the time the battle ended, nearly 24,000 men were killed, wounded, or captured — more than all the Americans killed in all the wars that had been fought until that time.

Shiloh is at least a two-hour drive from both Memphis and Nashville. The best time to visit the battlefield is the anniversary of the battle, when Union and Confederate re-enactors camp there. But Shiloh is a great place to visit anytime. We’re going to show you around a bit.

The first question you should ask yourself is “why would anyone fight a battle way out here?” Here is what led to it:

In February 1862, the Union Army captured Fort Henry on the Tennessee River. This left the river undefended, and during the next few weeks the Union Army and Navy began working their way upstream with little resistance. Eventually, the commanders decided that they would try to take over Corinth, a small town in northeast Mississippi where two railroads intersected.

The Union ground forces were divided into two parts. One, led by General Ulysses S. Grant, set up camp across the river and nine miles upstream from Savannah, Tennessee. There wasn’t much there except for a few farms and a small church called Shiloh (a Hebrew word that means “place of peace”). Grant’s forces waited for another army, led by General Don Carlos Buell, that was coming down from Nashville. The plan was for the two armies to join, then march together to Corinth.

General Grant apparently had no idea that his troops might be attacked while it camped near Shiloh. If he had, they would have dug trenches and gotten ready for an attack. But he didn’t, so they drilled and relaxed while they waited for Buell.

Confederate General Albert S. Johnston had other ideas. Knowing what the Union generals had in mind, General Johnston decided to attack the Union army before dawn on April 6.

It wasn’t easy to move an army through the soggy marshes, thickets and flooded streams near the river; because of this, it took longer for the Confederate Army to attack than first planned. But they still had the element of surprise, and in the early part of the battle they forced the Union army back. Many Union soldiers were eating breakfast when the attack came. After they abandoned their camps, many of the attacking Confederates stopped to eat the food that the Union troops left behind.

The Confederate army earned every yard. One regiment from Mississippi started across a valley with 425 men; by the time they reached the other side they only had a little more than 100.

When General Grant arrived from Savannah, he found his troops retreating and panicking. Some of them were cowering below a cliff on the riverbank, having seen enough of a real battle.

There was, however, one place where the Union Army held fast. A Union general named Benjamin Prentiss ordered his men to defend a sunken road with a field in front of it. For nearly seven hours Confederate soldiers came in waves to attack the Union men along the road. The barrage of bullets that they encountered was so great that the attacking troops started calling the area the “Hornet’s Nest.”

There were eight separate Confederate charges over the course of five hours, and it is believed that around 2,400 Confederates were killed or wounded in the process. Then the Southern army set up big guns and started firing those toward the Sunken Road. Finally, at about 5:30 that afternoon, General Prentiss surrendered his remaining 2,200 troops (about half the ones he had started with). But in the process Prentiss’s men bought time for the larger Union force closer to the Tennessee River, at a place called Pittsburg Landing. They had time to regroup and reorganize.

While the fighting at the “Hornet’s Nest” was taking place, something else occurred that may have turned the Battle of Shiloh. General Johnston was shot in the leg by a musket ball and bled to death near where this monument is now located. He almost certainly would have lived had he had any medical attention, because a simple tourniquet around his leg would have kept him alive. But the men who were with the general at the time (which included Tennessee Governor Isham Harris) didn’t realize that the general was hurt until several minutes after he was shot. Johnston thus became the highest ranking general from either army killed during the Civil War.

The night of April 6 was a sad night.

Thousands of soldiers from both armies lay on the battlefield dead or injured; there were so many bodies that entire fields were covered with them. There is a small pond on the battlefield. So many injured men crawled here to drink from it that night that there is a story that the water turned red. It became forever known as the Bloody Pond.

Nightfall was, however, a good thing for the Union Army. Here, at Pittsburg Landing, the Union Army received badly needed reinforcements that night from General Buell. And, by the way, the arrival of troops by way of boat brings up a rather important point about the Battle of Shiloh. The Union troops had gunboats and troop ships to support them with gunfire and bring them reinforcements. The Confederate troops had no naval presence during this battle.

This marker, located in the cemetery, is believed to be where Union General Ulysses S. Grant spent the night of April 6. It rained that night, and Grant originally tried to spend that night in a cabin by the river. But the cabin had been turned into a field hospital, and the cries of the wounded kept him awake, so the general walked out and slept while leaning against an oak tree that used to be here.

By the next morning, the reinforced Union Army was a lot larger than the Confederate Army. General Grant then ordered his troops to advance and recapture the territory that they had lost the day before. And they largely did just that. By the middle of the day the Confederate Army retreated back towards the South, having lost thousands of their comrades, but having gained a large number of Union prisoners.

Here are some other things that you will see at Shiloh:

Take advantage of the history presentations, such as this one on drummers.

If you study the cemetery, you will find evidence of what a bloody battle this really was. Close to the river you will find these six gravestones, all representing the six Wisconsin color bearers (or flag carriers) who were killed in the battle.

If you study the cemetery, you will find evidence of what a bloody battle this really was. Close to the river you will find these six gravestones, all representing the six Wisconsin color bearers (or flag carriers) who were killed in the battle.

You may also find this tombstone, which marks the final resting place of one of the drummer boys killed in battle. By the way, drummer boys were often as young as 10 years old.

Now one thing you will notice is that there aren’t many Confederate soldiers in the cemetery. Why is this? Mainly because the field of battle was left in control of the Union Army, which made some effort to bury its dead in an organized fashion, but buried most of the Confederate bodies that they found in mass graves. Here is one of those mass graves.

By the way, the existence of the Confederate mass graves and the Union cemetery shouldn’t give you the impression that these are the only places bodies are buried. Thousands and thousands of men died here, and in the days that followed the battle there wasn’t time to bury them all, certainly not in an organized fashion. It is believed that there are men buried all over the battlefield.

The United Daughters of the Confederacy raised money to build this beautiful monument in 1917.

The United Daughters of the Confederacy raised money to build this beautiful monument in 1917.

Every figure and depiction of this monument means something. According to a national park service web site, for instance, the figure on the far left (closest to you in this picture) represents the Confederate cavalryman, whose hand is opened in frustration. “He is eager to help, but [he and his horses] cannot penetrate the undergrowth” of the battlefield.

Also, you will notice that there are 11 heads on the right side of the monument, 10 on the left. The right side represents the first day of battle, and how eager the Confederates were to fight. The heads are bowed on the left side, representing the defeat of the second day, and the fact that one of them is missing represents the deaths of so many Confederate soldiers.

The face in the middle of the monument is that of General Johnston.