Some of the more important events in Tennessee history didn’t happen in Tennessee.

On March 27, 1814, an army led by Andrew Jackson and consisting of, among others, nearly 2,000 volunteer soldiers from Tennessee, attacked a Creek Indian stronghold in what is now Tallapoosa County, Alabama.

The victory by Jackson’s army at Horseshoe Bend brought an end to the Creek nation’s power east of the Mississippi River. It made Jackson famous. It started the process under which the state of Alabama was created.

So why did the Battle of Horseshoe Bend take place?

It happened during the War of 1812, a war in which the British encouraged Native Americans to fight against the United States.

It happened a couple of years after the Shawnee chief Tecumseh came south and encouraged other Native American tribes to fight against whites.

It occurred at a time when the American government was trying to “civilize” Native American tribes and build a new road through Creek territory, which many Creeks did not want.

Not all of the Creeks took up arms against the American Army in 1813 and 1814. Those that did are referred to as Red Sticks.

(So, much like the Chickagamaugans were the warlike tribe within the Cherokee nation, the Red Sticks were the warlike tribe within the Creek nation.)

Starting in February 1813, there were several military engagements between the Red Sticks and Americans. Prior to Horseshoe Bend, the best known of these took place at Fort Mims, near Mobile, Alabama, in August 1813.

At Fort Mims an army of about 1,000 Red Sticks killed an estimated 250 settlers, including women and children. “Remember Fort Mims” became the rallying cry for Americans to fight the Creeks.

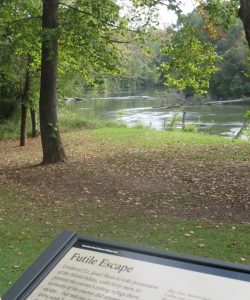

Horseshoe Bend from above. The highway you see, crossing the Tallapoosa River, was obviously not there in 1814. PHOTO: National Park Service

In March 1814 the Red Sticks, led by a warrior named Menawa, set up a stronghold near a Creek town called Tohopeka. It was surrounded on the west, south and east by the Tallapoosa River, and protected on the north by a long log barricade.

Menawa’s thousand warriors believed they were safe from attack. But only about a third of them possessed muskets. The rest were armed with bows, arrows, tomahawks and warclubs.

Jackson’s army of 3,300 men consisted of several parts: soldiers from the U.S. Army; Tennessee militia; 500 Cherokee warriors; and about 100 Creek warriors opposed to the Red Sticks.

Jackson decided to blast the log barricade using two cannons, then attack the barricade with the infantry. If and when the Creeks tried to retreat across the river, they would be shot by 600 sharpshooters from Tennessee and by the Cherokee warriors, who he sent to surround the village on the other side of the river.

General Jackson, wary of deserters and undiscipined soldiers, told his men that he would not tolerate disobedience.

“Any officer or soldier who flies before the enemy without being compelled to do so by superior force and actual necessity shall suffer death,” he told his men.

Things didn’t go according to plans.

At 10:30 a.m., Jackson’s cannons opened fire. For nearly two hours, shells landed on or near the barricade and did not appear to blast holes in it, as Jackson had hoped they would.

But as soon as they heard the cannon fire, the Cherokee and Creek warriors allied to the Americans decided to cross the river and attack on their own.

General Jackson then ordered his infantry to attack the barricade on foot.

General Jackson then ordered his infantry to attack the barricade on foot.

Fighting was fierce; most of it hand-to-hand.

“Arrows, spears and balls were flying,” one participant later wrote, “swords and tomahawks were gleaming in the sun.”

Creek warriors at the barricade were soon overwhelmed. Those that weren’t killed immediately retreated–some to protect their village from the Cherokee attack that had come from the rear and some to get away from the American assault in the front.

Creek warriors at the barricade were soon overwhelmed. Those that weren’t killed immediately retreated–some to protect their village from the Cherokee attack that had come from the rear and some to get away from the American assault in the front.

The battle soon deteriorated into a slaughter. Many Creek warriors found it impossible to defend their village and, unwilling to surrender, tried to cross the Tallapoosa River. Practically all of them who tried to cross the river were shot by the sharpshooters from Tennessee.

So many died crossing the river, in fact, that the river is said to have been red with blood.

Today we estimate that about 800 Creeks died — the largest death toll for Native Americans in a single battle in American history.

On the American side, 26 men were killed, while 18 Cherokees and five Creeks who fought for the Americans also died.

A few months later, in August 1814, the Creeks signed what is known as the Treaty of Fort Jackson, ceding much of what is now central and southern Alabama and southern Georgia to the American nation.

Now for a few points of interest about this battle:

- * Practically none of the Creek warriors surrendered, but chose to fight to the death. Many Creek women and children in the village of Tohopeka did surrender, however, and most of them were later transferred to an encampment in Huntsville, Alabama.

- * The American army apparently left the dead Creek warriors, unburied, on the battlefield. They buried their own dead (other than Major Montgomery) in the Tallapoosa River.

-

* Among the Americans who attacked the Creek barricade that day was a young officer named Sam Houston. He fought on in spite of the fact that he was hit by an arrow in his thigh, then was hit twice by bullets. Houston was later elected governor of two states: Tennessee and Texas.

- * During the Indian Removal of 1830s, many Cherokees bitterly recalled how Cherokee warriors fought with Andrew Jackson at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. Many said at that time that a Cherokee warrior named Junaluska actually saved Andrew Jackson’s life at Horseshoe Bend.

Whether this it true or not, Cherokee warriors certainly played an important part in the American victory at Horseshoe Bend. In fact, two of the young Cherokee warriors who fought that day were John Ross and Major Ridge–both of whom would play important roles in the fate of the Cherokee nation in the 1830s.

It’s a long drive from Tennessee to Horseshoe Bend National Military Park, which is near Alexander City, Alabama. If you can’t visit Horseshoe Bend, there is another way bring the battle to your classroom, and that is to get a copy of a DVD that illustrates the battle. To do so, call the park at 256-234-7111.

And now for some photos from March 27, 2014–the 200th anniversary of the battle:

The Muscogee Creek nation was out in full force. Here (on the right) are some of its members who were present.

Here (on the left) are some of the members of the Muscogee color guard–all U.S. military veterans.

For the first time since BEFORE THE BATTLE, members of the Creek tribe did ceremonial dances on the former site of the village of Tohopeka.

Some of the participants were old, some not so much.

History Bill got to meet George Tiger, who was the principal chief of the Muscogee Nation.