In 1832 things were looking bad for the Cherokee nation. Stripped of their rights in the state of Georgia, members of the tribe moved their seat of government from New Echota in northwest Georgia to Red Clay, just across the Tennessee state line.

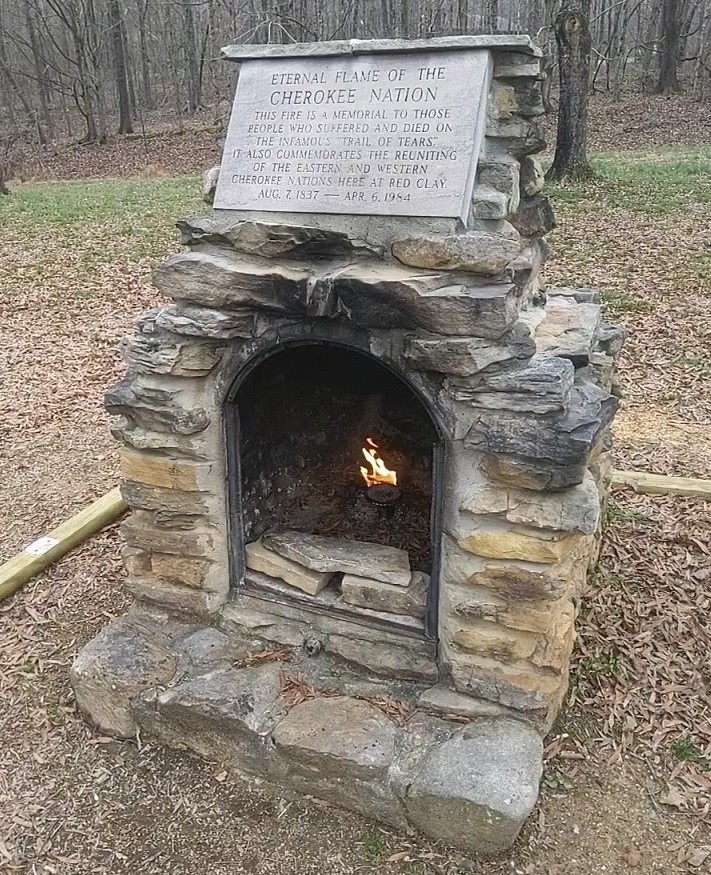

Red Clay would not be the Cherokee capital for long. Only six years later the tribe would be sent west on a journey we now know as the Trail of Tears.

The Red Clay grounds are now a state historic park. We’re going to show it to you and tell you its story.

The Cherokee tribe once controlled a large part of the southeast United States. But as white settlers moved west and forced their way onto Cherokee land, Cherokee leaders signed away or sold large chunks of the land, sometimes under political or military pressure.

As you can see from this map, by the 1820s the tribe only controlled part of what is now southeast Tennessee, southwest North Carolina, northeast Alabama and northwest Georgia.

In spite of the loss of so much of their land, most Cherokees assumed they would be allowed to stay in this section of the country forever. After all, they had lived peacefully with the American government ever since the brutal Nickajack Expedition of 1794.

In spite of the loss of so much of their land, most Cherokees assumed they would be allowed to stay in this section of the country forever. After all, they had lived peacefully with the American government ever since the brutal Nickajack Expedition of 1794.

Many Cherokees had fought with the American army and Tennessee militia at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend against the Creeks.

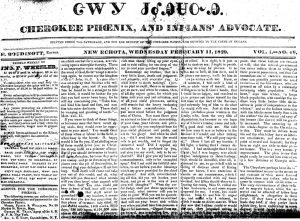

The Cherokee nation had largely adopted white ways: becoming farmers, taking on a democratic form of government under a constitution, adopting Christianity, and even creating a written language.

By the 1820s Cherokees were more likely to be literate in the Cherokee than white settlers in this part of the country were to be literate in the English language. Cherokees frequently went to church. They even had a written newspaper, The Phoenix.

In 1828, however, two things occurred that sealed the fate of the Cherokee nation east of the Mississippi River.

First, gold was discovered on Cherokee land in Georgia, resulting in a massive encroachment by white settlers onto Cherokee property.

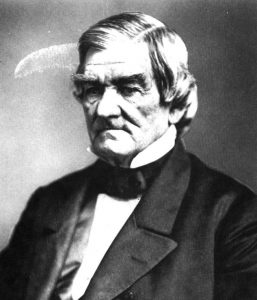

Then, Andrew Jackson was elected president. Though he could be kind to individual Native Americans, Jackson did not believe Native American ways could peacefully blend with the ways of the settlers. He immediately pursued a policy of removal–forcing the Cherokees off their land and relocating them to settlements west of the Mississippi River.

Here’s where Red Clay comes into the picture: by 1832 the Georgia legislature had taken away all Cherokee legal rights, taken the Cherokee’s land and made it illegal for Cherokees to hold political meetings.

At that point the tribe moved its capital to a site just north of the Tennessee/Georgia state line known as Red Clay. There was a spring on the site called Blue Hole Spring that is still there today. There were no structures there, so they quickly built a council house and a few cabins.

A council was a time when the Cherokee people came together to meet and for their leaders to discuss things important to the tribe. Councils generally lasted between two weeks and a month.

The Cherokee had 11 separate councils here at Red Clay between 1832 and 1838.

These councils were held in desperate times for the Cherokee people. In spite of President Jackson’s insistence that they would have to leave, the Cherokee people still held out hope that their principal chief, John Ross, would be able to work out a deal under which they could stay. The Cherokee people thought they had a good legal case, since the U.S. Supreme Court under John Marshall had ruled that the 1830 Indian Removal Act was unconstitutional.

However, it was here, at Red Clay, that the Cherokees realized that the U.S. Supreme Court ruling would not help them. Here they also learned that a small group of Cherokee leaders (led by Major Ridge) signed the so-called Treaty of New Echota, which purportedly sold all the Cherokee land east of the Mississippi to the American government.

After John Ross learned about this treaty, he tried hard to get the U.S. Senate to reject it (an effort that failed by one vote). After that effort failed, more than 15,000 Cherokees (practically the entire tribe) signed a petition protesting the treaty and claiming that those who signed it did not have the agreement of all the Cherokees. But the American government used this treaty as final justification to force the Indians off their land.

The stages of Cherokee removal are shown in this series of stained glass windows at the

Red Clay visitor center.

In the fall of 1838 the U.S. Army began forcing Indians into staging camps near the Tennessee River. From there some went downriver on boats, while others marched northwest.

Today we estimate that 4,000 of the 15,000 Cherokees died either along the way or in the holding camps, which is one reason we refer to it as the Trail of Tears.

The trip was especially hard on the elderly and young children. Those who died were usually buried in unmarked graves which are now all over Tennessee and Arkansas.

After they left, all the structures that had been built at Red Clay were torn down, and the land became part of a privately owned farm. In 1979, its owner sold it to the state of Tennessee to be used as a historic park.

Among the structures you will find there today are a visitor center, a replica of the council house, a replica of a small Cherokee farm, and a replica of some of the small cabins that were built there during Red Clay’s short time as Cherokee capital.

The small farm replica is meant as a reminder of what life was for many Cherokee by the 1820s — a generation after the tribe adopted so many aspects of white culture.

However, there wasn’t actually a farm here when Red Clay was the Cherokee capital.

We have visited Red Clay several times — once during its annual Cherokee Days festival in early August.

Here are some pictures:

The visitor’s center contains a small museum and theater where you can see a film about the Red Clay story.

Among the performers we saw was this girl who sang a Christian hymn in Cherokee.

This is a good reminder to us that, by the time they were using Red Clay as their capital, most Cherokee had adopted the Christian religion.

A dance was performed called the “Bear Dance.”

You can see why it is known as the Bear Dance!

There was also a group of reenactors depicting Cherokee life in the 1820s and 1830s

Feeling the need to exercise, we went on a short nature trail to the overlook, shown here.

We don’t recommend this hike be taken during an August heat wave. It was hot; there were too many mosquitos and chiggers; and you can’t see much from the overlook because of the trees. Probably a great hike in the fall and winter, though.

We don’t recommend this hike be taken during an August heat wave. It was hot; there were too many mosquitos and chiggers; and you can’t see much from the overlook because of the trees. Probably a great hike in the fall and winter, though.

Feeling even more need to exercise, we walked to the edge of the park, to the Georgia/Tennessee state line. Here we found this marker put here by the Georgia chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Feeling even more need to exercise, we walked to the edge of the park, to the Georgia/Tennessee state line. Here we found this marker put here by the Georgia chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution.

We also want to remind you of one thing about this park: It is remote and they don’t sell food there. So bring a picnic lunch.